They Call Him the Honey Man

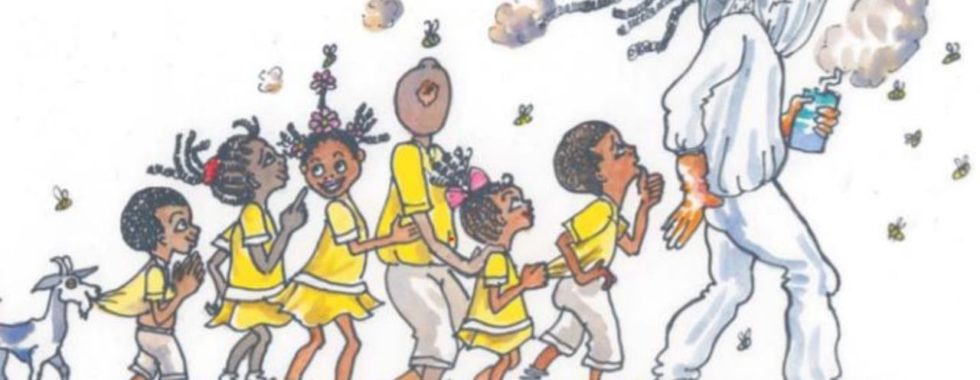

Dropping lightly from the battered black pickup, piled high with hive boxes and trailing an airborne chorus of bees, he lopes into the school yard. It doesn’t take long for a train of children to form behind the veiled Rasta, draped in white and wreathed in a cloud of smoke that bellows from a tin contraption in his left hand. They call him the Honey Man.

When registering for a beekeeping course in 1996, Alistair “Twaado” Jacobs was still a carpenter, little knowing he would become Antigua’s icon for all that is “sweeter for the sting”. Today, as the Field Officer of the Antigua Beekeepers’ Cooperative,

he provides a lifeline to some fifty beekeepers and honey hunters. He also teaches the six week course for “newbees”, and shares his vision for Caribbean honey with children at school and in summer camps. What looks like useless bush to the land developer is literally a valley flowing with ‘you know what’ in the eyes of the Honey Man.

West Indian honeys, from Trinidad and Tobago in particular, have been winning international prizes for many years. Perhaps their secret is the great diversity of flowering plants in the islands. Continental honey is often produced by bees foraging on just one extensive crop, such as alfalfa.

By contrast, the Caribbean honeys have something of the unruly Soca rhythm. Different types of nectar parade during the year like Carnival troupes: a dry season red, then a wet season gold, light coloured when the mangroves blossom in the salty wetlands and then dark.

Although there are as many as 1000 flowering plant species in Antigua and more than 3000 in Trinidad & Tobago, bees can be quite particular. Jamaicans swear that their bees will ignore all other flowers to feed on the flowers of the genip, a fruit tree introduced by the Arawaks.

In St. Lucia and Dominica, the favourite honey is gathered when the savonette, unique to the Antilles, is in flower. At Christmas beekeepers on Antigua & Barbuda eagerly anticipate the week- long bloom of logwood, a dyewood introduced from Latin America by the buccaneers in the 16th century.

Bee keeping and honey hunting go back to Egyptian times but bees were only introduced to the Caribbean from the Old World in the 17th century. The latest arrivals are the African honeybees, stars of 1980s exploitation movies, escaped from experiments in Brazil, gradually invading Central America and the southern States. They reached Trinidad, but remarkably, not Tobago.

It is part of the Honey Man’s job to patrol Antigua’s ports for evidence of both invasions of African bees and bee diseases, from which Antigua has always been free until, on 4th March, 2005, he discovered to his horror a tick- like parasite sucking on the bees inhabiting a trap at the capital’s Deep Water Harbour. The varroa or vampire mite had finally arrived in Antigua.

This is a pest that has destroyed most of the wild bees around Europe and the Americas during the 1980s and has been island hopping through the 1990s. According to Tomas Mozer, regional bee inspector in Florida, “We expect it to wipe out at least half of the colonies on the island, like it did in Barbados, St Lucia and other islands.”

Antiguan beekeepers want to keep their reputation for the finest organic honeys. Unlike their US counterparts, they won’t be dousing the hives with chemicals to combat the mite. “We are going to let nature select a resistant bee” says the Honey Man, with that unmistakably Rastafarian confidence. “No chemicals here. Bee wise!”